Published date

Written by

TOKYO, Nov 1 — “I’m holding an illustrated book of cheeses,” says a delighted Tomoyo Ozumi, a customer at a growing kind of bookshop in Japan where anyone wanting to sell their tomes can rent a shelf.

The concept brings back the joy of browsing real books to communities where many bookstores have shut, and gives readers more eclectic choices than those suggested by algorithms on online sellers, its proponents say.

“Here, you find books which make you wonder who on earth would buy them,” laughs Shogo Imamura, 40, who opened one such store in Tokyo’s bookstore district of Kanda Jimbocho in April.

“Regular bookstores sell books that are popular based on sales statistics while excluding books that don’t sell well,” Imamura, who also writes novels about warring samurai in Japan’s feudal era, told AFP.

“We ignore such principles. Or capitalism in other words,” he said. “I want to reconstruct bookstores.”

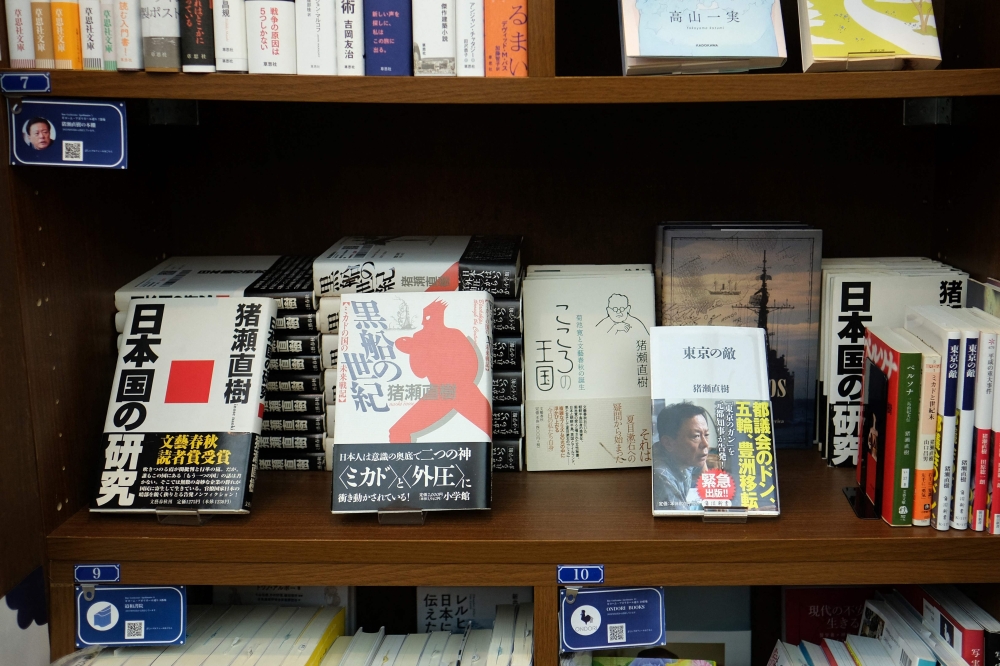

His shop, measuring just 53 square metres, houses 364 shelves, selling books — some new, some used — on everything from business strategy and manga comics to martial arts.

The hundreds of different shelf renters, who pay ¥4,850-¥9,350 (RM140-RM267) per month, vary from individuals to an IT company to a construction firm to small publishers.

“Each one of these shelves is like a real version of a social media account, where you express yourself like in Instagram or Facebook,” said Kashiwa Sato, 59, the store’s creative director.

Cafes and gyms

For now, his store Honmaru — meaning the core of a Japanese castle — is only in Tokyo, but Imamura hopes to expand to other regions hit hard by bookstore closures.

A quarter of Japan’s municipalities have no physical bookstores, with more than 600 shutting in the 18 months to March, according to the Japan Publishing Industry Foundation for Culture.

Imamura in 2022 visited dozens of bookstores that have managed to survive the tough competition with e-commerce giants like Amazon, some by adding cafes or even gyms.

“But that is like putting the cart before the horse. Because if a gym is more profitable, 90 per cent of the shop may become a gym, with 10 per cent for bookselling,” Imamura said.

Crowd-pullers

Rokurou Yui, 42, said his three shelf-sharing bookstores in the same Tokyo area are filled with “enormous love” for shelf owners’ favourite books,

“It is as if you’re hearing voices of recommendations,” Yui told AFP.

Owners of regular bookstores put books on their shelves that they have to sell to stay in business, regardless of their personal tastes, he said.

“But here, there is no single book that we have to sell, but just books that someone recommends with strong passion and love for,” he said.

Yui and his father Shigeru Kashima, 74, a professor of French literature, opened their first shelf-sharing bookstore, called Pvassage, in 2022.

They expanded with two others and the fourth opened inside a French language school in Tokyo in October.

Passage has 362 shelves and the sellers help attract customers with their own marketing efforts, often online.

That is in contrast to conventional bookstores that often rely on owners’ sole sales efforts, he said.

On weekends, Yui’s store sometimes “looks as if it were a crowded nightclub with young customers in their 10s, 20s, 30s” with edgy background music playing, he said.

Customers and shelf-owners visit the bookstore not only to sell and buy books, but to enjoy “chatting about books”, he said.

Japan’ industry ministry in March launched a project team to study how to support bookstores.

“Bookstores are a hub of culture transmission, and are extremely important assets for the society in maintaining diverse ideas and influencing national power,” it said. — AFP